By Jamil Khoury, Silk Road Rising Founding Artistic Director

September 1, 2015

I think a lot about the representation of Muslims, particularly the representation of Muslim Diasporas, and especially the representation that occurs on stage. But what happens on stage rarely begins on stage. Images have a way of filtering up, gestating first in mainstream media before seizing dramatic license. The mass media manufactures images of Muslims, mainstream culture turns them into stereotypes, and playwrights—ideally—create context and nuance. So indulge me in a little theorizing and a propensity for thinking in threes. You’ll see what I mean in a moment.

Let’s begin by analogizing twentieth-century representation of gay men and lesbians with twenty-first-century representation of Muslims. Let’s presume we are referring to North American representation. And, for the sake of subjective clarity, let it be known that I am a theatre producer, a writer, a cultural activist, an "out” gay man, a mixed blood Arab American of Syrian Christian heritage married to a Pakistani American Shi’a Ismaili Muslim. In other words, my household is an ISIS/Al Qaeda worst-case scenario. We’re a Wahhabi nightmare. We’re not supposed to exist. Now that I got that out of the way, on to the analogy.

Historically (and some may argue to this day), gay men and lesbians were represented through three lenses: psychology, religion, and law. As objective categories, psychology, religion, and law may seem innocuous enough, but as tools for defaming and injuring queer people, they are, in fact, quite lethal.

Psychology told us we were crazy, pathological, incapable of sustaining relationships, prone to self-destructive behaviour, and that we were feeding an addiction rooted in childhood trauma. Our love was impulsive, narcissistic, and never “real.” If we were men, we had overbearing mothers and distant fathers. If we were women, we’d had bad experiences with men.

Religion told us we were sinners, we were evil, we defied nature, threatened families, signified social decadence and moral decay. In short, we were incompatible with righteous living, and we were plague carriers—stricken ill through divine retribution. Not even God liked us.

The law told us we were criminals, social deviants, predators, susceptible to blackmail, gender non-conforming, and of dubious citizenship. We were indecent, obscene, and corrosive to morale, and we were child molesters. The FBI, CIA, Pentagon, and State Department classified homosexuals as security risks and potential fifth columns. In many respects, we were yesterday’s Muslims.

Psychology, religion, and law essentially branded gay men and lesbians; and society and public policy embraced the brand, hook, line, and sinker. We led tragic lives that begat tragic ends. Murder, suicide, or AIDS. Take your pick.

Building on that legacy, I would argue that Muslims today are also represented through three lenses. Those three lenses are national security, patriarchy, and liberalism.

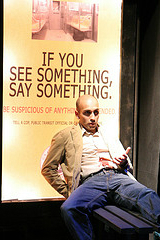

Discourses on national security tell us, implicitly and explicitly, that Muslims threaten us. Muslims are violent. Muslims will kill us. They’re prone to terrorism. They blow things up. Muslims pose an existential threat to our nation and to our way of life. Even a liberal Muslim and a moderate Muslim are but extremists-in-waiting.

Patriarchy, we are told, has a best friend in Islam. So much so that Islam and patriarchy are commonly conflated. Think male subject, female object, and our subject is possessive, controlling, and cruel. There may be misogyny and sexism in all religions, but Islam is patriarchy on steroids. If men beat and rape women, then Muslim men beat and rape women even more. Common wisdom invented a consensus: Islam is bad news for women, Muslim women are universally oppressed, and Muslim feminists are rarely to be found.

Then there’s liberalism, with its emphasis on liberty, equality, civil rights, electoral politics, freedom of religion, protected speech, and achieving a balance between individual desires and collective responsibilities. In popular culture, Islam gets depicted as the antithesis of liberalism: not only incompatible with liberal values, but at war with those values. And this adversity is not simply ideological, or even theological; it may in fact be biological. Muslims possess an innate, inborn aversion to all things liberal. They are, by nature, authoritarian, tyrannical, void of empathy, averse to self-criticism and introspection, volatile, and understanding only of force. Pluralism, power sharing, tolerance for opposing viewpoints, and respect for the other are all signs of weakness in the Muslim mind.

Now I am well aware that the politics of challenging Muslim representation can quickly devolve into the politics of proscribing and policing Muslim representation, which is a death sentence for artists of all backgrounds. Counter-representation relies on dominant representation as its canvas. We are still simply responding.

The challenge becomes to respond less and to create more, and to stop ceding power and legitimacy to narratives that reinforce people’s worst fears about Muslims. Not as an exercise in “celebrating” or “purifying” Muslims, not as an apology or act of redemption, not as a nod to political correctness, but as a commitment to our own artistic integrity, and to the recognition that with representation comes responsibility. For example, if towards the end of a play, a Muslim male character beats up a woman or commits an act of terrorism (or both!), be very wary. Intentionality matters and it is painfully transparent.

What is exciting to me is how we as theatre artists address these lenses of national security, patriarchy, and liberalism. I’m not saying that we can’t apply these lenses to Muslim characters or to plays that are somehow about Muslims. Judging from my theatre company’s production history, I’d be an absolute hypocrite to even suggest that. And of course we can’t ignore the cultural zeitgeist, with all its fears and phobias.

But being the good liberals that we are means we’re sometimes susceptible to the allures of an unexamined liberal racism: first humanize the Muslim character, then demonize him; make him nuanced, then make him predictable; make us like the brown man, then make us fear him. Certain audiences may eat this up, but as an artistic director, these are tropes I studiously avoid.

Muslim playwrights, in particular, should avoid pandering to audiences’ worst fears about Muslims in hopes of attracting mainstream approval. Exploiting one’s “insider status” and “lived experience” as cover for making gross generalizations about Muslims is bad practice. Criticize, call out, air dirty laundry, demand change, by all means, but success needn’t come at the price of “authenticating” arguments peddled by those who inflict harm on Muslims.

I want theatres to support playwrights in creating new narratives about Muslims, and to pay attention to existing narratives that already acknowledge, interrupt, and subvert my three lenses. Egyptian-American playwright Yussef El Guindi and Tunisian-Swedish playwright Jonas Hassen Khemiri succeed brilliantly at this, wielding tremendous irony, deception, and poetic justice along the way.

El Guindi and Khemiri never shy from interrogating the relationship between the profiler and the profiled, ascribing sympathy and suspicion to both, and enabling their characters to compete for our benefit of the doubt. They confront the threat of Islamist terrorism, be it real or imagined, through the complex, self-conscious vantage points of the Muslim suspect and those trained to detect him. By illuminating a “Western gaze” over the gender politics and perceived anti-liberalism of Muslim communities, and by casting a watchful eye over colonial impulses within Western feminisms, these artists deconstruct and expose the folly of a “with us or against us,” “clash of civilizations” sort of world. El Guindi’s plays Back of the Throat, Our Enemies, and Language Rooms and Khemiri’s plays Invasion! and I Call My Brothers all stand out as prime examples.

Surely there is room for a plethora of Muslim representations, emanating from mass media to Broadway to storefront theatres. And it is all too often the dearth of representation, and its incumbent burdens of representation, that focus our attention on the negative, stereotypical, and formulaic. After all, representation we fear or condemn today may seem banal or ahead of its time a generation from now. But there’s no reason why the evolution we have witnessed in queer representation cannot have parallels in Muslim representation, albeit on its own terms. With conscientious artists leading the charge, my triumvirate of Muslim representation—national security, patriarchy, and liberalism—will be rendered reactive, reductive, and woefully dated. Hopefully sooner rather than later.

PLEASE NOTE:

Jamil Khoury's Mass Media Muslims: A Three Lense Theory of Representation was first published in alt. theatre: cultural diversity and the stage (summer 2015), a professional theatre journal published by Teesri Duniya Theatre in Montreal, Canada. It grew out of papers delivered by Khoury at Silk Road Rising (“Muslim American Artists: Reshaping the Narrative,” March 9, 2015) and Princeton University (“The Dramaturgy of Political Violence: Ayad Akhtar, Aasif Mandvi, and Muslims on U.S. Stages,” April 6, 2015).

Click here to read the essay in PDF format.